Jonathan Swift said that when a great genius appears, all the dunces will be in confederacy against him. It was with this quotation Santiago de Molina was introduced on his last visit to our university. He took the time share his reflections and tips on the way forward for architecture in an area apparently so devoid of genius – everyday settings.

He’s worked with some of the great names of Spanish architecture, such as Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza or the Pritzker Prize-winning Rafael Moneo, and he has juggled teaching with his professional work at his own studio for many years. He’s also active in research, carrying out studies which consistently aim to make architecture and culture more accessible to everyone. Evidence of this can be seen in his books such as Hambre de Arquitectura and Collage y Arquitectura.

We’re in no position to be able to judge whether Santiago de Molina’s a genius or not, but he certainly writes like one. Just take his blog Múltiples Estrategias de Arquitectura as an example: it shows not just his mastery of the subject, but also real inspiration and ingenuity.

A journey through art and architecture: an invitation from Santiago de Molina

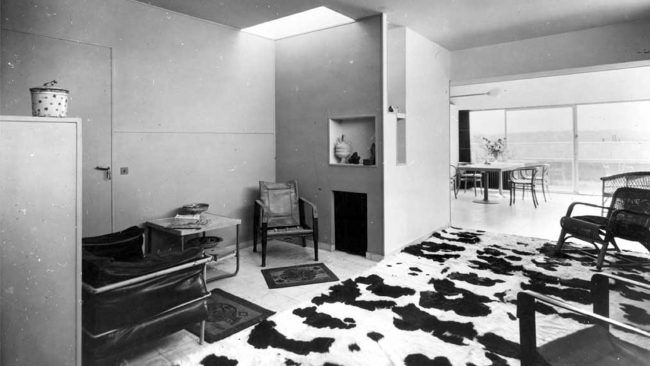

De Molina invites us to join him on a visual journey through architecture, with our first stop taking in the work of the great Mies Van Der Rohe. This architect’s work is the epitome of refined yet strident modernity and it is also the perfect example both of the mark architecture can make and of the life that springs up in and around it. In some photographs of him where he appears him a more relaxed mode, we an image of him which is different from the one he typically transmitted: that of looking impeccable, perfectly posed and battle-ready for the fight for modernity.

In these photos we see the private side of Van Der Rohe, completely relaxed and so different from his usual ramrod stiffness. This contrast should give us pause: do the great masters also need domesticity? Is modernity really incompatible with the everyday? Or, more broadly, when did the relationship between modern architecture and the everyday break down?

Daily routines have never received the same respect as other, more eye-catching, seemingly greater – or certainly more grandiose – themes. However, there are numerous examples in the history of art of artists who have been able to dignify the simplest or most mundane facets of life. For example, we see this in Dutch painting and still lifes: paintings where the protagonists are objects that, thematically and even objectively, are trivial. We see this too in portraits, many of them of obscure people: women wearing no adornment, going about their daily business; or soldiers in quiet moments of rest, enjoying some free time.

Who can forget that, by portraying such people and such moments, focusing on the ephemeral nature of lives, masters such as Johannes Vermeer built their later reputation? These artists were masters of what is both intimate and mundane: portraying the habits of the inhabitants of a place.

“I WOULD DEFINE ARCHITECTURE AS THE THOUGHTFUL MAKING OF SPACE.” – LOUIS I. KAHN

But one day it all changed. It was no longer about reflecting reality, but about apparent reality. With modernity, photography pushed painting into second place and became the true art of the moment. Le Corbusier himself exploited this new technique and used it in his work. Photographs of his projects include everyday objects, seemingly more or less randomly taken: kitchen utensils, decorative features, or prosaic tools leaning against a wall.

So why did he take these pictures? Is this an early form of product photography? Did he want to see what his dwellings looked like with people living in them? Or did he simply want to transmit emotion? With these objects, casually yet carefully positioned, Le Corbusier sought to promote the idea of comfort.

In the 50s, architecture sought to reconnect with the everyday, but this time in a completely new way. Since then, architects have sought to understand the language of everyday life so as to give shape to their work. As architects, we must accept the everyday for what it is and use it as the basis for our work. Yet, more often than not, we don’t pay enough attention to it.

An architecture of reconciliation

What about now, in this age of postmodernist architecture? The use of technology in the home is now pervasive, with smart devices such as Alexa or Roomba, and new trends in the design of spaces affect our behaviour. The kitchen is no longer the place where we cook, nor a place for the family to come together: it’s a place we pass through, in which both our route through and the time we spend doing so need to be optimized, whether or not we do need to cook or get together with other family members.

We are surrounded by technology. Smart appliances in our homes collect data to find out what our behavioural habits are. We think they’re helping us to manage our daily lives better, when in fact this huge amount of data about our ordinary lives is being fed into the cloud. We’ve even begun to sell our private lives to tourists, turning our houses into no-star hotels.

Given all this, what should architecture’s role be? It must reconcile the home with daily life and Santiago de Molina thinks he knows how we should do it.

Rethinking the room

Traditionally, rooms are not spaces that have been thought about too much, and yet they are a basic part of our domestic and private life. Louis I. Khan said that architecture is about the making of space. And at the heart of all this space and of these rooms are the people who live in them. Our private lives have no direct connection to a space surrounded by walls: could there be a more private moment and space than that which Millet shows to us in his work The Angelus?

Rooms should be conceived of as the heart of the personality and personal and collective privacy of the people who live in them. Because our private lives are based on an intimate relationship between us and the space we live in.

In a letter to Émile Bernard, Van Gogh said that, probably, life was not flat, but round. And that a room needs a centre – a psychological centre, that is.

Rebuilding the wall

Current trends seem to be for walls to disappear, but can we afford that to happen? Walls are a basic part of our reality and they provide us with shelter and a framework within which to weave our lives. They physically separate us from the outside but their physical characteristics can vary: are walls made of cloth still walls? If they can be, then are not curtains also walls which also allow us to mark rooms in a distinctive way and don’t they protect us and allow us to see and yet not be seen?

Reoccupying the corners

We may owe the recovery of corners of rooms to the Swedish company IKEA. For Santiago de Molina, this giant of low-cost decoration has mastered the reinvention of corners by means of the seemingly impossibly labyrinthine floorplan of their stores. Hundreds of absurd square metres designed to confuse customers and create nooks and crannies into which real life can creep in. We feel safe in these little corners – we can live in them. And what if we thought of a room as being made up of corners, rather than walls?

Relocating the doors

In the 16th century, rooms had a lot of doors and yet now the trends are moving in the opposite direction: we see open, diaphanous, light-filled, empty spaces. But the do4or is what determines where the corners of the room will be and how important they are.

We should think carefully about and re-invent every door, because it represents an opportunity: we can open it or close it. It’s the physical place at which exchanges happen and decisions are made: we can go through it or stay where we are.

Reconsidering ornaments

For Santiago de Molina, today’s domestic ornaments are just objects which fill space. They’re objects which enable us to change those spaces and even the passage of time within our homes, but the way in they are arranged can come into conflict with our everyday lives. Research has shown that disorder encourages creativity and problem-solving. That’s why it’s important to understand the relationship between design, construction and the arrangement of objects. Even if we run the risk of revealing how little we know when we try to do so.

De Molina believes in the responsibility that comes with being an architect, which derives from our role as the agents of transformation of the abstract into the tangible. This is the reverse process of what painters do, those same ones he admires and refers to so often on his blog.

“As architects, we can’t force people to do what we want them to. We can’t impose a particular lifestyle on them through our designs,” says Alfonso Díaz, a lecturer in Architecture at our Technical School. “Our role must be to help people, by suggesting but never by imposing.” Of course, Santiago de Molina will always be a role model for us in this.