In 1919, German architect Walter Gropius founded the Staatliche Bauhaus in the city of Weimar. This year commemorates the centenary of the first school of truly modern art, an institution that was responsible of one of the most innovative and revolutionary artistic trends in the history of architecture and design: the aesthetic, the legacy and the influence of the Bauhaus continues, one hundred years later, to be relevant.

Who was Walter Gropius?

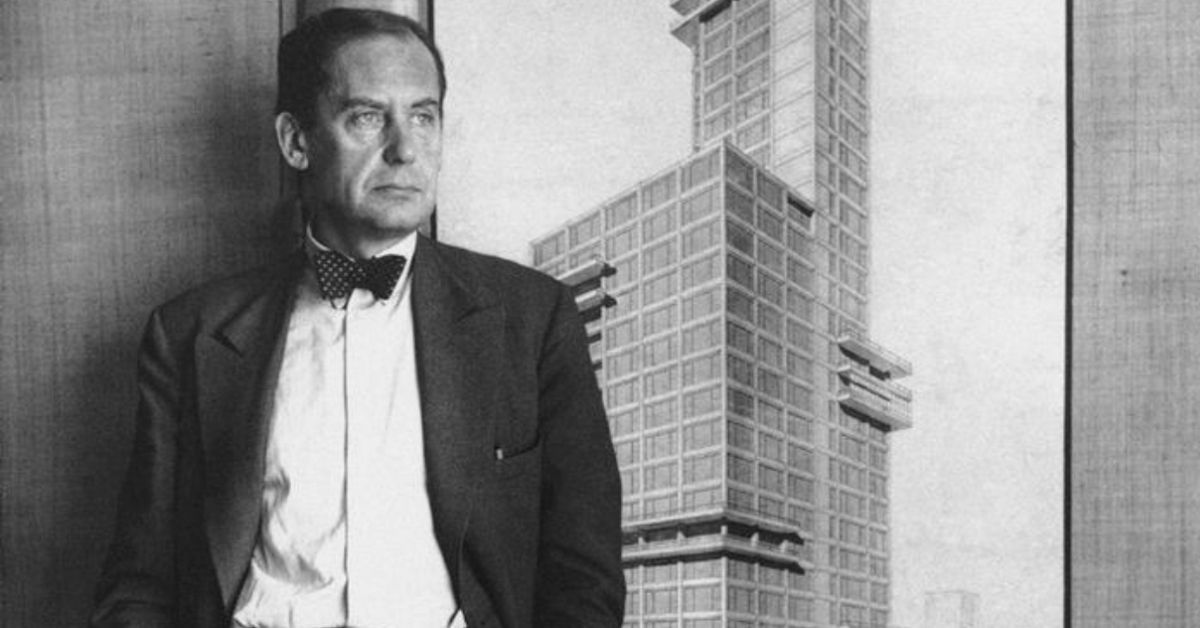

Born in Berlin and descending from a long line of architects, Walter Gropius, along with Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, is possibly one of the most influential architects from the first half of the 20th century. His interest for functional design always led him to developing industrial sites and housing complexes that could be built in a fast and economic way.

From 1907, Walter Gropius collaborated with a group of artists, architects and designers from the Deutscher Werkbund, Bauhaus’ predecessor. Based in Munich, this group liked to create simple, restrained and functional objects that unite design and the best of the industrial processes that were being developed during this era.

When Gropius was chosen as the director of two newly created art schools in Weimar, he took all of the Werkbund influences and, from 1919, used them as a driving force behind what he called Bauhaus (“house under construction”): a school dedicated to closing the gap between craftsmanship and industrial art. In a short space of time, the centre separated itself from other similar institutions and continued to develop its own personality, and to a larger extent to revolutionise the teaching methods.

IN THE BAUHAUS THEY CREATED PRACTICAL, SIMPLE AND USEFUL OBJECTS APPROPRIATE FOR THE NEW TRENDS OF THE 20s

The students from the school had to follow a study plan, which included materials related to fine arts as well as the latest design techniques to ensure that the projects were commercially viable. At the beginning of their education they had immersive courses related to the study of materials, theories of colour and form as well as the different theoretical and practical aspects of craftsmanship. After this first cycle, the students had a more specific timetable with workshops in areas such as basketmaking, pottery, typography and wall painting, always under the supervision of an artisan or an artist.

Thus, as a hub for avant-garde art, the Bauhaus soon caught the attention of artists, architects and experimental creators such as Paul Klee, Mies van der Rohe and Josef Albers, who all came to become part of the teaching staff.

Weimar, Dessau and Berlin

The concept that this school was founded upon was completely radical for the time since it was looking to reinterpret and unify all art forms under the same roof. Walter Gropuis made his intentions clear in the Bauhaus Manifesto (1919), in which he described this idea of uniting art and design with architecture, sculpture and painting in a unique creative expression.

The school moved around headquarters from its opening up until it closed in 1933 when the Nazis considered its aesthetic ideology to be inappropriate and labelled it as disturbing.

The first of the head quarters was in a small place in Weimar, which has recently opened as a museum dedicated to its legacy. After the demise of the Weimar Republic, Dessau took in the Bauhaus during its era of greatest splendour. It was in this city that Walter Gropius developed a building, which has since become an icon, exemplifying the principals of the school.

“THE MIND IS LIKE AN UMBRELLA, IT WORKS BEST WHEN IT IS OPEN,” WALTER GROPIUS

The Bauhaus building contains innovative elements that have subsequently been incorporated into more contemporary architecture, the materials, distribution and spatial logic. The principals of functionalism were combined with pioneering materials such as glass, steel and concrete in order to create a complex where the school, workshops and housing coexisted.

Because of its architectural value, the Bauhaus building is a historical reference point of undeniable importance in the renewal of the arts in the 20th century, because of this; it is now on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Then, in 1930, the Bauhaus and its director, Mies van der Rohe, was forced relocate to Berlin. However, due to the difficult political situation in Germany along with pressure from the Nazis, they were forced to close down. A little later, Walter Gropuis and many of the school’s members were forced to emigrate, mainly to the United States, due to harassment from the Nazis. Already in exile, his vision and work reached and influenced future generations of designers and architects.

Design and industry: the Bauhaus style

At the end of the 19th centaury Germany was looking to replace the United Kingdom as the main European Economic Power. The new industrial production methods allowed German artisans and designers to mass-produce and contribute to the economic growth. Industrial products where therefore an important factor in developing the external image of the country: in a short space of time, German products started to become renowned for their excellent design, functionality and quality of materials.

“ART IN INDUSTRY” WAS THE BAUHAUS MOTTO: THEY HAD TO DESIGN FUNCTIONAL OBJECTS THAT COULD BE MASS PRODUCED

The design of buildings and spaces quickly began to be influenced by the Bauhaus style, which is defined by its simple lines and open spaces that are always decorated with refined furniture. Simplicity, clean designs and an industrial concept of production are the fundamental characteristics of this style. Pieces like the Wassily chair, named by Marcel Breuer in honour of the abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky, are an example of this.

Although the Bauhaus style is flooded with very diverse disciplines such as tapestry design and typography, it’s the furniture and product design have perhaps been some of their best work.

Names like Josef Hartwig, Peter Keler and Mies van der Rohe have left their mark on all types of chairs, lamps, cots and chessboards. Versatile pieces, some with a very geometric appearance, others with a much more minimal appearance or reduced to more basic forms, almost all of them have become icons of modernity.

Something that all of the objects coming out of the Bauhaus have in common is that pragmatism and usefulness over power beauty. Or at least beauty without reason. Because of this, a lot of the pieces have very simple geometric shapes, which allow for their combined use and facilitate their storage, like with Josef Albers famous nesting tables.

The Bauhaus women

Although in the 30s their names were unfairly pushed to the side, the Bauhaus did also train women who contributed to the legacy of the school in an outstanding way. Women like Otti Berger, Anni Albers, Gunta Stölzl and Marianne Brandt, among others, unfortunately are not as well known as their male counterparts even though they contributed on the same level.

During the centenary of this foundation exhibitions and films like the German Lotte am Bauhaus, inspired by the life of Alma Siedhoff-Buscher, draw attention to and defend these pioneering women and their work in designing products, furniture and textiles.

One hundred years later and the Bauhaus movement continues to be recognised as one of the most influential movements in architecture and contemporary design, as well as visual and applied arts. And the cultural calendar is full of events and activities to commemorate this anniversary… a fantastic occasion to discover its legacy!